The Washington Post Inspired Life - Perspective | ||

|

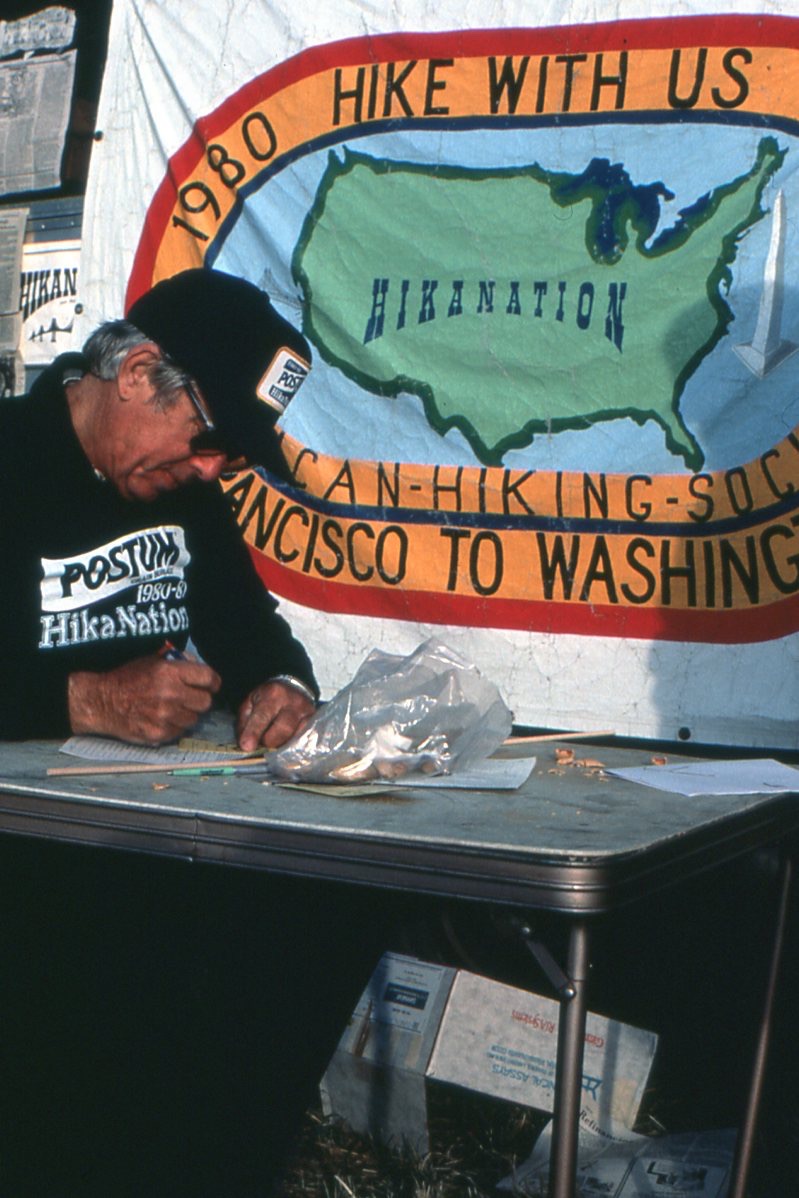

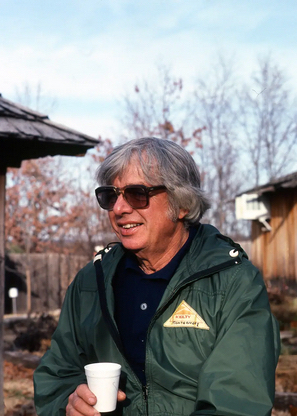

I crossed the U.S. on foot with a group of strangers 40 years ago. It was one of the best decisions of my life. By Stacey Waring - May 25, 2021 at 6:00 a.m. EDT  Stacey Waring in 1981 in Virginia as part of the HikaNation trek across the United States. (Reese Lukei Jr.) A small write-up hidden on the back pages of a Newsweek magazine led me to the town of Las Animas, Colo., in the fall of 1980. As a hiking enthusiast from Springfield, Va., I was elated when I read that a group of backpackers had just left San Francisco and planned to cross America together on foot. I immediately made plans to join them three months later in this small town near the Kansas border. I really didn't know what I was getting into, of course. Yet 40 years later, I realize this decision was one of the most consequential of my life. Conceived by Jim Kern, creator of the Florida Trail, and Bill Kemsley, founder of Backpacker magazine, the trek was designed to attract support for hiking trails and a transcontinental East-West path. Called HikaNation, the journey would take around 14 months and 4,200 miles to complete. A "pathfinder" in each state was responsible for charting the route and determining campsites. The adventure had the support of the American Hiking Society and other organizations. But as the group left California on April 12, 1980, much was in doubt. Would there be calamities or death? What if some got lost? Would the hikers get along? Could this trek really succeed?  Hikers resupply and study maps near Roanoke, Va. (Reese Lukei Jr.) The reality soon became clear. We hiked about 12 to 15 miles a day with packs on our backs weighing close to 50 pounds. The trip tested us as we walked our way through scorching heat in Nevada, icy streams in Arkansas, below-zero winter days in Kentucky and knee-deep snow in Virginia. Along the way, hikers left, returned, and were joined by new members such as myself. We went through the highways, byways and trails of America, crossing 14 states and D.C., where we were met at the U.S. Capitol by a phalanx of flags and a congressional delegation before heading into Anacostia and eastward.  HikaNation trekkers arrive at the U.S. Capitol on May 13, 1981. (Stacey Waring) Finally, on May 27, 1981, there were no more steps to take as we threw ourselves into the Atlantic surf at Cape Henlopen, Del., hugging and crying, stunned at what we had accomplished over the thousands of miles. Of the 80 who began with the intent of completing the trip, 37 hiked the entire nation, while many more, like myself, had done a significant part of the journey.  On May 27, 1981, the HikaNation group finally reached the shores of the Atlantic Ocean at Cape Henlopen, Del. They had hiked about 4,200 miles over 14 months. (Reese Lukei Jr.) Today HikaNation remains one of the largest groups to ever complete such a feat. It was not just a physical endeavor but a social experiment. Keeping peace and harmony among people who, by nature, are independent fell mostly to the parental figure of the trip, Monty Montgomery, a retired Air Force colonel who was part Enforcer-of-Few-Rules and part hugging grandfather. Monty drove a beat-up Airstream trailer parallel along our route and met the group when roads allowed, providing water, mail and great morning coffee. He was the glue that kept us together. | ||

| ||

Not surprisingly, the hike attracted adventurous young dreamers who mingled with retirees and those disenchanted with their careers, as well as a few leaving bad marriages. Adolescents befriended grandparents, while small-town hikers debated politics with urbanites. The group set up camp in Dodge City, Kan., in October 1980. (William Ewart) A few were asked to leave by the group for causing problems, but later returned with more wisdom. The youngest participant, Jiamie Pyles, born months before the trip's start, was pushed across the entire country by her father, first in a stroller, then in a rig concocted of PVC pipe.  Jiamie Pyles being pushed by father "Gomer" Pyles on May 13, 1981, in D.C. (Reese Lukei Jr.) John Stout, the oldest hiker at 69, was a retired machinist who perfected the daily nap, then would bypass us 20-somethings on the trail.  John Stout raises the U.S. flag in celebration before a cheering crowd at the U.S. Capitol on May 13, 1981. (Stacey Waring) HikaNation worked because at the core was a deep concern for each other and a shared mission. Mothers on the hike routinely cared for a young man who rarely spoke a word for months. We gave generous amounts of food and supplies to each other. And when one hiker nearly died deep in a Utah canyon, others came together to carry him out and to a hospital. We respected both our autonomy and interdependence, giving each other not only support but distance. I frequently changed hiking partners to gain a new outlook, hear gossip or chat about political news (always delayed, we did not know Reagan was shot until two days afterward). In winter, tent-sharing became a necessity to stay warm as much as an amorous experience, but one marriage did come out of the trip as did many relationships. We also came to embrace a country of which most of us had only read. Growing up in the Virginia suburbs, I had never seen Kansas, Oklahoma or Kentucky. But at age 26, as I spent months crossing these states by foot, I came to better understand the complexity of our nation. People we met were universally friendly and proud of their towns. Church groups provided dinners, while locals would drive by with hands extended offering soda or water.  One of many small-town stops in the fall of 1980 (Stacey Waring) A shopkeeper in Arkansas opened his shoe store for us one cold night. A pizza restaurant provided "all you can eat" status to us until they ran out of food. A woman in Oklahoma made a herculean effort to return my lost camera without even knowing me. And when I went to pay for a coat that was cleaned in Kansas, the clerk refused my money, tearfully noting that, "this is my way of going with you."  Hikers take a break in the snow on the Appalachian Trail in March 1981. From left are Jeannie Harmon, Rob Burns, Cindy Bain and Phil Atkins. (Stacey Waring) After the journey's end, I assumed that our group would disperse and return to our prior lives, rarely meeting again. Rob Burns, our youngest hiker at age 14, went back to high school (his school had given him permission for the trip), while John Stout ran a marathon. Though some struggled to find purpose, most found career paths, emboldened by new confidence. After living out of a tent for nearly a year, my prior stressors did not seem as difficult. I no longer minded cold or wet weather and realized I did not need a TV. I became a clinical psychologist and spent 36 years working in the community-mental-health field in Northern Virginia, where my husband and I raised two sons.  Hikers celebrate at a 10-year reunion at Cape Henlopen in May 1991. (Tim Geoghegan) But I missed many of my comrades immensely. After the first year, we held a reunion in Arkansas, and another at five years - then 10 years, 20, 30. All the gatherings found us clamoring to reconnect. While we briefly heard about babies born and jobs lost, most of the conversations held were about the hike itself, as if we needed to relive it one more time.  Thirty-five-year anniversary of the hike, in Estes Park, Colo., in September 2015. (Courtesy of Stacey Waring) Of those who hiked at least part of the trip, at least 25 have passed away. Most of us who hiked in our 20s are now retired, and the irony that we are nearing John Stout's HikaNation age is not lost on anyone as we are humbled by knee and hip replacements. Some still regularly hike, albeit shorter distances, and a few of us come together for alumni treks each summer.  Stacey Waring during a 2019 HikaNation alumni trek on John Muir Trail in California. (Tim Geoghegan) On May 27, 2021, I'll again remember the bonds that have kept most of us together for four decades when I return to stand at Cape Henlopen's shores with a few others. What good fortune I had to have once picked up a magazine that led me to this "family on foot." I learned that sometimes it's okay to take a leap of faith on humanity and yourself. It might be one of the best decisions you ever make. Note: Stacey's article was digitally reproduced with permission from her; awaiting The Washington Post's approval. Additional website links (mainly after the third paragraph) were added to her story by William Ewart. An additional photo of Monty Montgomery (by Rex Halfpenny) was also added. Return to The Progression of HikaNation | ||

|